BLOG

Kuniyoshi and his impact on Traditional Japanese Tattooing

Many would recognize Kuniyoshi as one of the most iconic Japanese woodblock print artists, yet he is also credited with influencing another visual art form, that of traditional tattoo designs. These are still a source of inspiration and are followed with precision by tattooists practising Japanese style tattoos worldwide. In this article, we look at how Kuniyoshi depicted the heroes of his time in woodblock prints and how he skilfully integrated tattoos in designs that still carry a meaningful message.

Kuniyoshi (1797 – 1861) was born in Edo (present-day Tokyo) as the son of a silk-dyer. It is said that he had a great interest in drawing from a young age. Even though Kuniyoshi eventually became a well-known and respected artist, the way to success and acknowledgment was a long struggle. His break-through came in 1827 with the series of ‘The 108 Heroes of The Tale of Suikoden’, which is based on a Chinese novel of the same name from the 14th century about brave rebels who fought against injustice and corrupt government officials. The story struck a sensitive chord within the common people of Edo, equally repressed by a military government and unable to openly show their dissent.

Most of the motifs that appear in the Suikoden tattoos are animal and floral designs, but mythical characters such as the god of wind, Fujin, or the god of thunder, Raijin, also appear. Furthermore, it is during the time of Kuniyoshi’s Suikoden series that different tattooing techniques and set-ups, the use of backgrounds and compositions found in modern Japanese tattoos arose.

It is assumed that Kuniyoshi himself might have been tattooed, which explains the high level of detail brought out by his designs. Nicknamed ‘scarlet skin’, some depictions of the artist testify to his playful nature. Few portraits of the artist exist, but they all show Kuniyoshi engaged in what he loved most – designing woodblock prints or teaching students. His clothes were richly decorated with patterns that may have been an indication of more designs hiding underneath. Because of the laws of the time, common people were restricted from wearing overly decorated clothing, yet Kuniyoshi was never afraid to walk a thin line and cleverly challenge rules in his own eccentric way.

Other students of Kuniyoshi drew sketches and used tattoos as a theme in their woodblock print designs and Kuniyoshi himself revisited the topic many times in other series with the same recognition. Kuniyoshi had a great passion for his craft, as is evidenced by the large number of prints he produced. He was a simple, straight-forward and broad-minded man who educated many artists including Yoshitoshi, Yoshiiku and Yoshitora. It is thought that Kuniyoshi particularly favoured Yoshitoshi, the best student among them who would become a great ukiyo-e master himself.

There is no mistaking the fact that Kuniyoshi’s interpretation of the Suikoden heroes had a major impact on tattoo culture in Japan. The intense swirling patterns, colours, and motifs, that are so iconic today might not exist as seen and practiced today were it not for this novel and the associated artwork. Consequently, many Japanese tattoo artists still render their own versions of popular themes, stories, or prints from Suikoden, becoming their own contemporary telling of a timeless story that has indelibly influenced their craft.

Origins of Moko

Are you interested in getting started on a traditional Māori tattoo but have always wondered where the practice comes from?

Mythological origins

Like other Māori rituals, those pertaining to tā moko derive from the mythological world of the atua (gods). The word ‘moko’ is thought by some to refer to Rūaumoko, the unborn child of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. Rūaumoko is commonly associated with earthquakes and volcanic activity and has been translated as ‘the trembling current that scars the earth’.

The story of Mataora and Niwareka

According to legend, Mataora, a rangatira who lived in Te Ao Tūroa (the natural world), married a tūrehu (spirit) named Niwareka, from Rarohenga (the underworld). One day he struck Niwareka across the face in a rage. She fled back to her homeland, as domestic violence was unheard of in Rarohenga. Mataora, overcome by guilt and love, set off to find her.

In Rarohenga he met Niwareka’s father, Uetonga, a rangatira descended from Rūaumoko, and a specialist in tā moko. Mataora was intrigued, for in his world moko was a temporary application of designs on the face. This form of adornment was termed ‘whakairo tuhi’ or ‘hopara makaurangi’, and used soot, blue clay or red ochre. Uetonga wiped his son-in-law's face to show the worthlessness of a temporary tattoo.

Mataora asked if Uetonga would apply moko to his face. The pain of the process was almost unbearable and as a consequence Mataora began to chant to Niwareka.

Niwareka was summoned by her sister, but Mataora, blinded by the swelling caused by the tattoo, was unrecognisable to her. However, she identified the cloak she had woven for her husband, pitied him for his suffering and greeted him with tears.

When his moko healed, Mataora asked Niwareka to return with him to Te Ao Tūroa. He promised Uetonga that he would not harm his daughter again as the moko he was now wearing would not rub off. As a parting gift, Mataora was presented with the knowledge of tā moko.

"Suminagashi" - Tattoos inspired by Traditional Japanese art

The art of paper marbling, or “Suminasashi” which translates to ‘floating ink’, appears to have began in Japan around the 12th century.

Various claims have been made regarding the origins of suminagashi. Some think that may have derived from an early form of ink divination (encromancy). Another theory is that the process may have derived from a form of popular entertainment at the time, in which a freshly painted Sumi painting was immersed into water, and the ink slowly dispersed from the paper and rose to the surface, forming curious designs, but no physical evidence supporting these allegations has ever been identified.

According to legend, Jizemon Hiroba is credited as the inventor of suminagashi. It is said that he felt divinely inspired to make suminagashi paper after he offered spiritual devotions at the Kasuga Shrine in Nara Prefecture. He then wandered the country looking for the best water with which to make his papers. He arrived in Echizen, Fukui Prefecture where he found the water especially conducive to making suminagashi. He settled there, and his family carried on with the tradition to this day. The Hiroba family claims to have made this form of marbled paper since 1151 CE for 55 generations

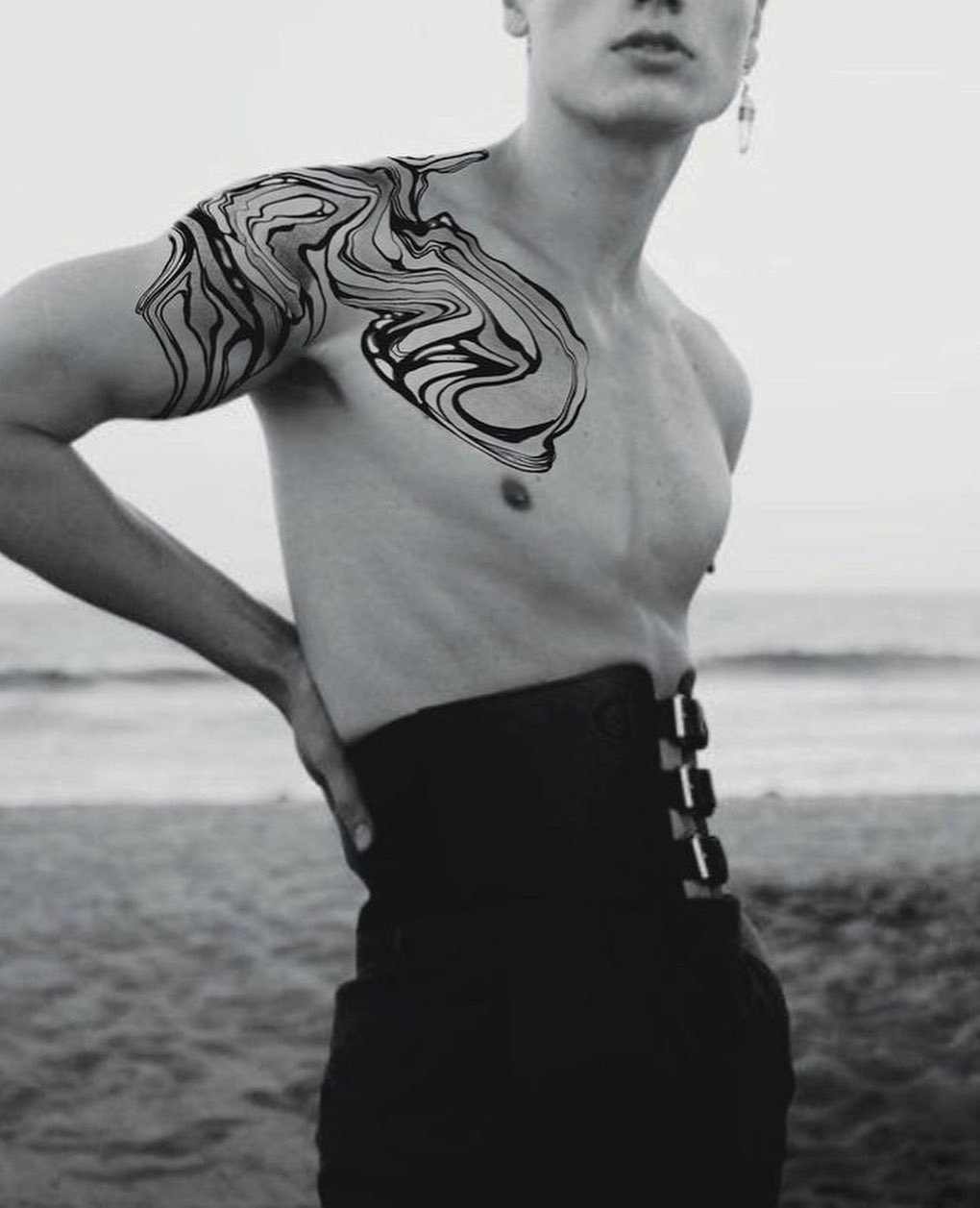

Our artist James Dean, who primarily specialises in black work tattoos has recently began experimenting with “Suminagashi” inspired tattoos. Incorporating black, light shading and negative space, James has placed these swirling designs on the human form that ebb and flow with the shape of the body. The result is interesting large scale concepts that highlight the human form.

Checkout some examples of the concepts in the gallery below, and if this is something that interests you definitely get in contact with the shop to book in a consultation

FLORAL MOTIFS IN TRADITIONAL JAPANESE TATTOOING - PART 5 CHRYSANTHEMUM

Traditional Japanese tattooing is typically created with three main elements, Background or “Gakubori”, the main subject matter, and an often overlooked complimentary floral element.

Floral elements are an important element of Traditional Japanese tattooing. They have a variety of meanings in Japanese culture, and when paired correctly with the right subject matter, they can create a harmonious tattoo rich with history and tradition.

In Japan, the chrysanthemum or “kiku” is associated with royalty–namely the emperor, who sits on what the Japanese have titled the Chrysanthemum Throne. It represents perfection and, in some interpretations, deity. It is also known as the “King of Flowers”. The chrysanthemum is also symbolic of happiness or joy, as well as longevity. Dragons can often be seen in Japanese tattooing paired with Kiku.

FLORAL MOTIFS IN TRADITIONAL JAPANESE TATTOOING - PART 4 PEONY

Traditional Japanese tattooing is typically created with three main elements, Background or “Gakubori”, the main subject matter, and an often overlooked complimentary floral element.

Floral elements are an important element of Traditional Japanese tattooing. They have a variety of meanings in Japanese culture, and when paired correctly with the right subject matter, they can create a harmonious tattoo rich with history and tradition.

The Peony or “Botan” in japanense culture is the king of flowers. Botan tattoos symbolise wealth, good fortune and prosperity. The peony is a strong symbol of beauty, fragility and transitory nature of existence. Furthermore, they depict that getting great rewards is only possible by taking great risks. Peony were imported to Japan from China for their medicinal qualities, “shishi” or foo dogs are also an import from Chinese culture, so pair well together for his reason. However there is also a folk tale of a shishi eating the peony and being cured of an illness, which adds to the reasoning behind this traditional pairing.